HOUSING DATA AND POLICY SNAPSHOT

What is Affordable Housing?

Cities and towns across the country face multiple intersecting housing-related challenges, including skyrocketing home prices, segregation, and mitigating and adapting to the effects of climate change. Our ability to address these issues can be complicated by ambiguity associated with certain terms and concepts, particularly those related to affordable housing. For example, affordable housing and housing affordability sound similar. However, these terms point to different sets of housing issues and solutions. To address these issues, DVRPC staff compiled a series of housing snapshots designed to help promote a shared understanding of the key terms, challenges, and concepts that are central to the housing crisis in Greater Philadelphia. This first snapshot, What is Affordable Housing?, explores the central ideas behind affordability and describes the most common types of government assisted affordable housing.

Defining Affordability

The concept of “affordability” can feel very subjective, but there is a set definition. The U.S Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) defines housing as affordable if it costs no more than 30 percent of an individual’s (or household’s) income to pay rent or mortgage, utilities, and other housing costs. According to this definition, households paying more than 30 percent of their income are considered “cost burdened,” meaning they could struggle to make other necessary payments and/or build wealth. Households paying more than 50 percent of their income on housing are considered severely cost burdened.

Concepts like cost burden help us understand and express the relative affordability of individual communities and the region as whole. The second snapshot in this series takes a closer look at cost burden to help us understand the extent of the housing crisis in our region. For now, we can highlight three important themes related to cost burden:

- Renters are at greater risk of being cost burdened. Nationwide, nearly 50 percent of renters spend more than 30 percent of their income on housing costs. By comparison, only 21 percent of owner-occupied households are cost burdened.

- African Americans and Hispanic households are disproportionately cost burdened.

- Cost burden is a relative metric; a high-income cost-burdened homeowner is less likely to be negatively impacted than a low-income cost-burdened renter.

Affordable Housing

Affordable housing refers to specific housing units that are owned and operated, subsidized, or incentivized by the government. These units are typically targeted to meet the needs of low- and very low-income households as well as those who need specific services. Although cities, towns, and counties can play an important role in the funding process for affordable housing, most of the financial support for affordable housing programs comes from the federal government.

Public housing and rental assistance programs, such as Housing Choice Vouchers and Section 8 Project-Based Rental Assistance, are the most direct ways that the federal government addresses housing needs among families with the lowest incomes. In each of these programs, participants pay approximately 30 percent of their income for rent and utilities and a federal subsidy covers the remaining costs. Other programs serve specific populations, including the Section 202 and Section 811 supportive housing programs for older adults and people with disabilities, respectively.

The lack of affordable housing is the defining feature of the current housing crisis, as the demand for public housing and rental assistance far exceeds the supply. According to research conducted by the National Low Income Housing Coalition (NLIHC), no state has an adequate supply of affordable rental housing for the lowest income renters. As such, most applicants for rental assistance face waiting lists that are very long or closed, and only about one in four low-income households eligible for rental assistance receive it. Nationwide, NLIHC estimates that there is a shortage of nearly seven million homes for households with low incomes.

Affordable Housing Programs

Public housing is the oldest and largest affordable housing program in the United States. Administered by HUD through grants to state and local public housing authorities (PHAs), the program builds and manages developments for very low-, low-, and moderate-income households. Public housing may be clustered in self-contained developments or scattered throughout a city or jurisdiction. The number of public housing units has fallen significantly since the mid-1990s as PHAs have demolished or removed units because of deterioration resulting from long-term underfunding or other factors.

The Housing Choice Voucher Program is the nation’s largest source of rental assistance. Individuals and families with low incomes use vouchers to help pay for privately owned housing. This program is facilitated by HUD and a network of state and local PHAs. For tenants to use housing choice vouchers, they must rent from a landlord willing to accept them. Tenants generally contribute 30 percent of their income for rent and utilities. The voucher covers the remainder of housing related costs up to a limit set by the housing agency based on HUD’s fair market rent estimates.

As opposed to vouchers, Project-Based Rental Assistance (PBRA) is tied to particular units and does not travel with individual tenants. Through the PBRA program, a private owner contracts with HUD to provide subsidized housing to low-income families, seniors, or people with disabilities. A monthly PBRA subsidy payment to the owner covers the difference between the tenant contribution and the cost of maintaining and operating the unit. Over the last few decades, federal housing subsidies have generally shifted away from these types of project-based subsidies and toward more decentralized household-based programs using vouchers.

The Low Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) program takes a different approach. Rather than providing housing subsidies, this federal program provides a tax incentive to encourage the construction or rehabilitation of affordable rental housing for low-income households. This tax incentive represents the largest source of federal assistance for rental housing and is designed to allow private for-profit and nonprofit developers to create affordable housing that is still financially sustainable for their organization. The program is administered by state and local housing finance agencies based on regulations issued by the U.S. Treasury Department. Investors participating in the program receive the tax credit over a 10-year period, and projects financed with LIHTC equity must remain affordable for a period of at least 30 years.

Where is Affordable Housing Located in Greater Philadelphia?

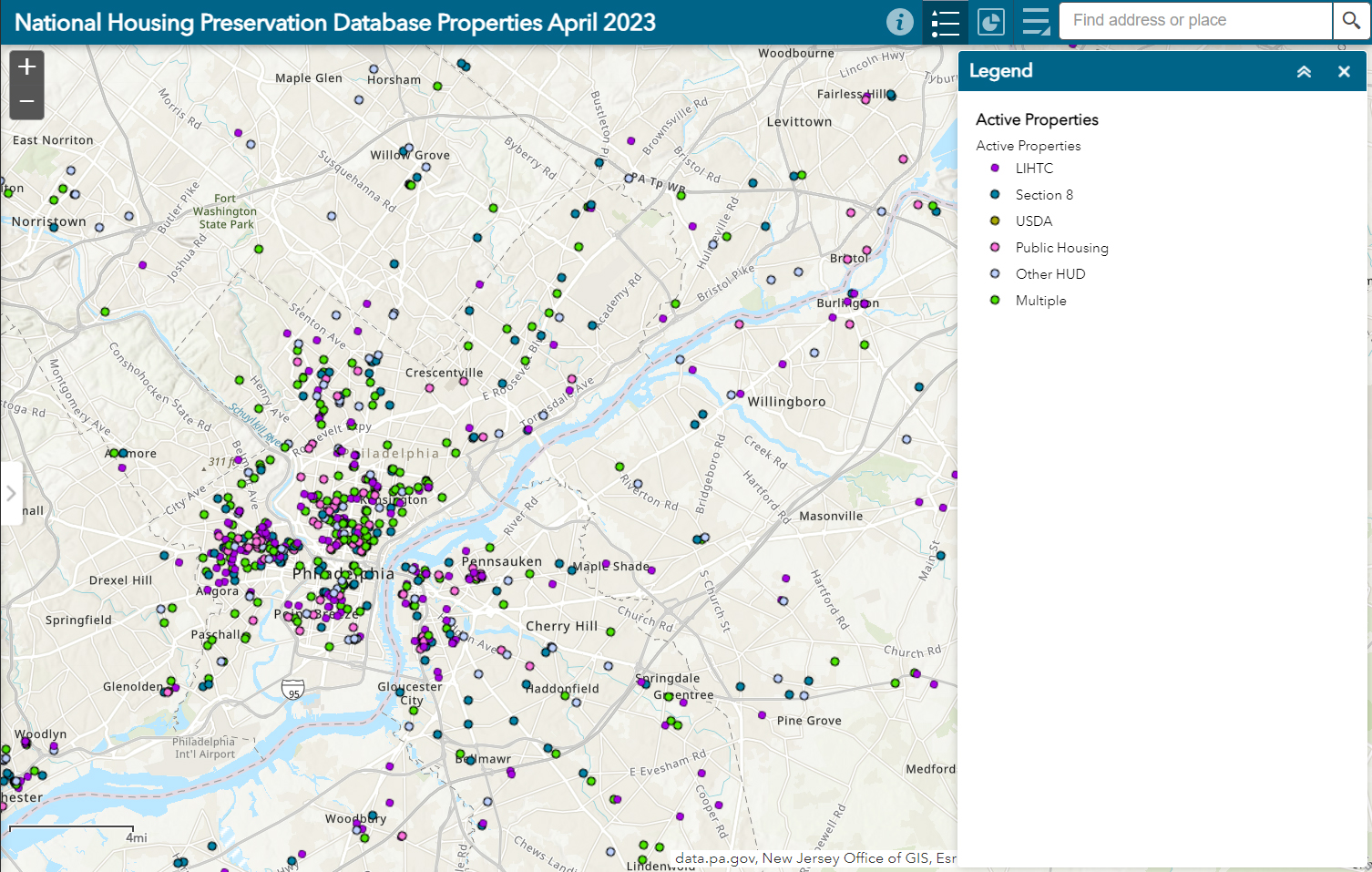

Tools such as the National Housing Preservation Database (NHPD) illustrate how the supply of federally-assisted affordable housing is distributed in our region. Created by the Public and Affordable Housing Research Corporation (PAHRC) and NLIHC, this database helps communities more effectively plan for and preserve their stock of public and affordable housing. The interactive mapping tool below allows users to view the location of several types of federally assisted rental housing, including public housing, project-based units, and housing constructed with LIHTC (Figure 1). The database does not include units subsidized by housing choice vouchers because there is no centralized database for that information.

Figure 1: NHPD Mapping Tool

According to the NHPD, as of April 2023, Greater Philadelphia was home to 1,050 federally assisted rental properties, totalling nearly 76,000 individual units. Figure 2 depicts the distribution of these units across Greater Philadelphia. Over 43 percent of these units are located in Philadelphia. The second largest concentration is located in Camden County, NJ. Nearly 20 percent of the region’s federally assisted housing units are located in the region’s four suburban Pennsylvania counties, while over 37 percent is located in the New Jersey counties.

Figure 2: Distribution of Federally Assisted Housing Units in Greater Philadelphia (April 2023)

Additional Key Terms and Concepts

Market rate housing units are those whose price is determined solely by market factors like supply and demand, as opposed to price limits imposed by state or local affordable housing programs.

Naturally Occurring Affordable Housing (NOAH) is housing that is not subsidized but offers low rents. NOAH frequently accounts for the majority of units affordable to renters with low and moderate incomes within a given jurisdiction. The supply of NOAH has steadily decreased over the past two decades, resulting in the displacement of people with lower incomes. Philadelphia’s Division of Housing and Community Development partnered with ULI Philadelphia and the ULI Terwilliger Center for Housing to explore this issue in a 2021 report entitled Preserving Philadelphia’s Naturally Occurring Affordable Housing.

Area Median Income (AMI) measures the median, or middle, household income in a specific geography. Updated annually by HUD, this number is the official figure used to determine income limits and maximum rent prices for government-funded affordable housing programs. AMI is not a single number, rather it changes based on the size of a household.

Fair Housing is a federally mandated right that prohibits discrimination in housing choice based on seven factors: race, color, national origin, religion, sex, familial status, and disability. The Fair Housing Act, passed in 1968, prohibits the discrimination of selling (including lending) or renting out housing based on characteristics related to these seven protected classes.

Jobs-to-housing ratios calculates the proportion of jobs relative to housing units in a specific area. Imbalances in this relationship can have important implications for housing and transportation costs. For example, a lack of housing, especially affordable housing close to job centers, will push demand for lower cost homes to more distant areas, increasing commute times and the share of household income spent on transportation costs.

The “Mount Laurel doctrine” is named after landmark court rulings by the New Jersey Supreme Court dating back to 1975 involving the namesake municipality in Burlington County. The doctrine states that every New Jersey municipality has a constitutional obligation to provide its fair share of low- and moderate-income housing. New Jersey has taken numerous steps over decades to implement these court decisions, including preparing three rounds of municipal housing targets. However, the process for determining each municipality’s housing obligations and appropriate enforcement mechanisms has been hotly contested since the program’s inception and will likely continue to evolve.

Despite some ambiguity regarding the current level of obligations, the intent behind this judicial doctrine means that New Jersey has taken a more aggressive approach to the provision of affordable housing than many other states. In Pennsylvania, the regulatory framework for combating exclusionary zoning is primarily established by the Pennsylvania Municipalities Planning Code (MPC). The MPC requires that municipalities provide for all land uses within their corporate boundaries and that zoning ordinances are designed to provide for “all basic forms of housing.”

Two Critical Threats: Expiration of Affordability Contracts and Climate Change

This shortage of federally assisted affordable housing units will likely become even more dire as government contracts for many subsidized rentals and LIHTC-funded units are scheduled to expire over the next decade. For example, Project-Based Section 8 contracts detail the length of time that property owners must maintain the affordability of certain units, typically 20 to 40 years, with the option to review for 1, 5, or 20 years. Units constructed with LIHTC funds must remain affordable for 30 years. After these contracts expire, property owners are allowed to rent those units at the prices that the market will bear. The LIHTC program was created in 1986 and made permanent in 1993. As such, many of the initial LIHTC units are approaching the expiration of their 30-year affordability restrictions. The NLIHC estimates that nearly 500,000 LIHTC-funding housing units across the country will reach the end of their affordability period by 2030.

In 2022, the issue of expiring government subsidies was at the center of the fight over the future of the University City Townhomes in Philadelphia. Tenants in 69 units at the West Philadelphia housing complex were forced to relocate after the building owner ended its federal contract to provide affordable housing on the site. The property owner planned to sell the site, highlighting the threats to the affordable housing stock in strong housing markets where real estate is appreciating rapidly. Ultimately, the City of Philadelphia has agreed to build 70 units of affordable housing on a portion of the site, and the displaced residents are receiving money as part of a settlement agreement from a federal lawsuit filed by the property owner against the city.

Although this settlement provides some resolution for the displaced residents of the University City Townhomes, the wave of expirations that is anticipated in the coming years ensures that these types of situations will become increasingly common. WHYY News estimated that more than 3,400 units—roughly 10 percent of all federally subsidized housing units in Philadelphia—operate under similar contracts that are set to expire over the next decade.

There are no easy solutions to this challenge, but housing advocates recommend that local and state policy makers and housing agencies attempt to intervene well in advance, typically between year 15 and 20 for a 30-year contract, to negotiate how affordability protections can be extended. For new units constructed with LIHTC funds, states can consider requiring or incentivizing longer affordability periods.

The housing crisis is also exacerbated by the increasing frequency and severity of extreme weather driven by climate change. Natural hazards and severe weather, including extreme heat and severe flooding, disproportionately impact low income neighborhoods and have the cumulative effect of reducing the supply of affordable housing and increasing housing and related costs. In our region, this issue came into focus in the aftermath of Hurricane Ida, when most of the properties destroyed by flooding were affordable housing units in low-income areas.

According to a 2019 report by the Center for American Progress, low-income renters are particularly vulnerable to being displaced by natural disasters. Affordable housing developments are particularly susceptible because they are often located in flood zones, where land is cheaper. They may be built with substandard materials that cannot withstand extreme weather, and, many times, the buildings themselves are older and already in need of repair. Furthermore, affordable housing units damaged by disasters are less likely to be rebuilt. This issue will only become more important with time. According to research from the Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University, about 40 percent of the nation’s occupied rental stock, representing 17.6 million units, are located in areas that will experience substantial annual losses from increasingly common environmental hazards.

Below are several tools that can help communities in our region assess their vulnerability to climate change and extreme weather.

- National Risk Index: FEMA designed the National Risk Index to help illustrate which communities within the United States are most at risk for 18 natural hazards.

- Climate Mapping for Resilience and Adaptation (CMRA): Developed in 2022, the CMRA helps communities assess current and future threats related to extreme heat, drought, wildfire, flooding, and coastal inundation.

- NJ ADAPT: Developed by Rutgers University, NJ ADAPT is a suite of data-visualization and mapping tools designed to help planners, community leaders, businesses, and residents understand and adapt to the impacts of climate change on people, assets, and communities in New Jersey.

- Coastal Effects of Climate Change in Southeastern PA: Built in 2019, this web application explores the potential impact of climate change on Pennsylvania communities along the Delaware River.

- Montgomery County Climate Change Potential Vulnerability Analysis: This online tool identifies areas of the county that are particularly vulnerable to the effects of climate change, including increased heat and storm events, relative to the rest of the county.